The Self-Serving Author (The Pros and Cons)

|

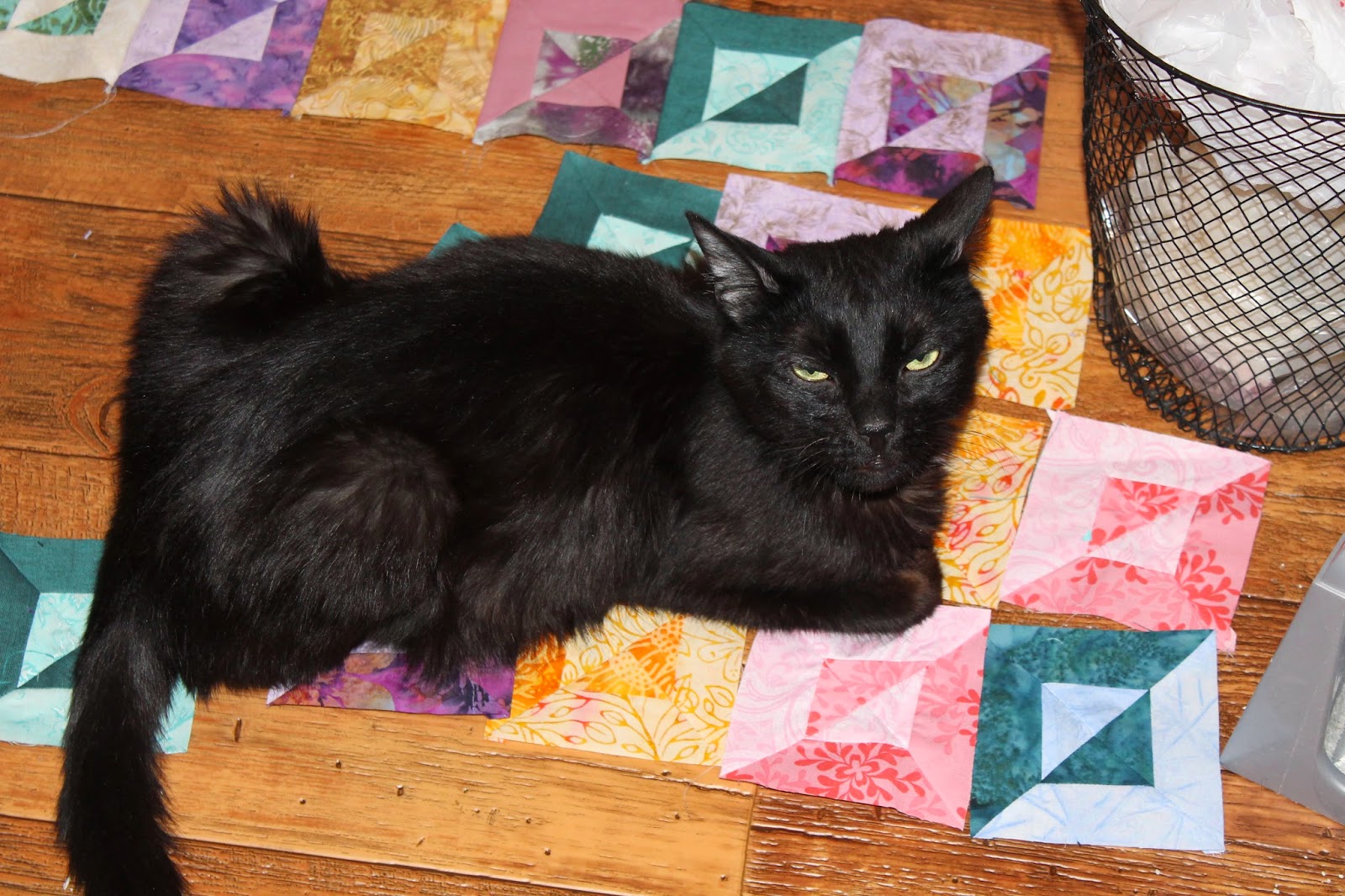

| Oh, I'm sorry. Are my needs disrupting you? |

When people ask me tips to improve their writing, my favorite saying is, “Don’t look like you’re doing what you’re doing.”

To which they smile and go, “What the hell does that

mean?”

It’s a smartass way to say though you want your character

to be epic, you don’t want the reader thinking, “Man, this author really wants

me to think this guy’s epic.” You want to be considered creative and clever not

have the reader thinking about how clever or creative you’re trying to be. You

want them to actually cry, not feel like you’re trying to make them cry.

Basically, you wrote something with a certain purpose in mind, but the reader

should never really be considering what that purpose is (unless he’s

deliberately analyzing the work.)

When you look at criticism, this is a fairly constant

subtext on their feedback. Meta-thinking is a gamer term in which the player

views the game as a game instead of as the character. It’s the difference

between thinking, “Obviously the programmer made some way to get across this

chasm, so let’s look for a lever,” versus, “Obviously the gnomes who made these

tunnels had some way to get across this chasm, so let’s look for a lever.”

This happens in writing too, and often having the reader

go meta is the most common source of a reader’s negative reaction. It’s not

what you did, but why she thinks you did it. It’s not that your prose is purple

as much as there doesn’t seem to be any benefit to take so much time and effort

in describing grass. When the reader starts to feel like the writer’s choices

are primarily to serve himself, she stops trusting him to avoid the heartache

that will come from an unsatisfying story.

So why do people go meta? It’s difficult, sometimes, to

say, and can be based on different contexts and personalities. What makes one

person go meta might not make another. There are usually two major reasons,

however.

First is there’s an obvious error in either real-life

rules or established in-world rules. The author makes a mistake in how gravity

works, or has the character fire a six-shooter seven times. This is the

foundation of the whole, “It’s about vampires and this is what you can’t believe?” argument. The reason why vampires

are okay but switching the words for stalagmite and stalactite aren’t is

because inventing magical laws is difficult and it benefits the readers’

imaginations. Switching stalagmite and stalactite is a mistake, easy to do,

that benefits no one.

Or the story broke its own continuity, in which it

clearly explained wizards can’t casts spells underwater then later has a wizard

casting spells in water with no clarification on the contradiction.

Second reason is more common but more complex. It occurs

when the author’s motivation outweighs the characters’. The protagonist does

something that the reader can’t empathize with at all, or that seems to

prioritize a motivation that he has never prioritized before—in other words, “acting

out of character.”

Empathizing is different than sympathizing. Sympathy is

where you feel for someone even though you can’t really relate. Empathy is

where you understand their feelings, where you feel what they feel and see

their motivation—even though you might not actually sympathize with them. You

can feel empathy and “get them” and yet still find them at fault for the event.

“Yeah, I could see myself punching him for that too, but that doesn’t mean you

should’ve done it.”

Let’s say a bartender decides to quit his job, but

instead of just telling his boss, he gets super trashed and acts like an

asshole. He chucks beers at people, swings from the chandeliers, etc.

First thing the reader is going to do is to try and

understand his actions. Even if she doesn’t agree with his reasons, there’s a

difference between not agreeing and not understanding. If, for example, he just

broke up with his girlfriend, realized that he had been a rule-following lap

dog for too long, the reader might understand the ridiculous reaction and

remain immersed. It’s a believable event.

But, what there doesn’t seem to be a reason? If the

reader can’t find any emotional or logical circumstances—he was paid decently,

he was cheerful, he didn’t have any conflict with anyone, didn’t mind his

boss—then the reader will turn to other places for the answer, usually the

author. And if the author gains an obvious benefit from the decision—the

bartender need to be put in jail so he could meet the character who would start

the plot—that’s when it looks like bad writing.

You have four levels of motivation: Character, Narrator,

Author, Reader.

There’s a lot to be said about this, but to sum up,

character motivation is why the character did what he did, narrator motivation is

why the narrator has chosen to describe this moment and in this way, author

motivation is why did an event happen at all, and reader motivation is the

reason why the reader wants to keep reading. Pretty simple.

Author motivation always exists, and it’s not a bad

thing. Everything you write, you write for a reason. Not necessarily a good or

rational reason, but you had a desired reaction to every choice—whether you

know it or not. It’s important, however, that the casual reader does not notice

the author’s motivation, that she’s thinking about the characters and is

staying in-world.

A lot of criticism comes from the author’s motivation outweighing everyone else’s. This could mean the character’s motive—an action doesn’t really seem characteristic as much as the end results are something that would benefit the writer—or more so, the reader—an action doesn’t enhance the reading experience as much as it makes the writer look good.

This is what is called the self-serving author.

Writing is a symbiotic relationship, and it doesn’t need

to be sacrificial. All writers are self-serving in a way, and it can lead to

the most entertaining sections. When you write what is most fun for you, when

you say what you really want to be saying, when you use writing to express

yourself, that’s when it will be most interesting for the reader. Generally

speaking, most of their enjoyment will come from an open and honest connection

with the writer.

But there are times when what benefits the writer and

what benefits the reader conflict, and in that case, the writer benefits from

considering his audience first and foremost. When it starts reading like he’s

trying to get something from the reader (admiration) without giving anything in

return (enjoyment), the reader starts to brace against the work.

For example, there is somewhat of a propensity to have

epically large numbers in sci-fi and fantasy. The vampire is a million years

old, the planet is a billion miles in circumference, the war killed trillions

of people. This is a prime example of being self-serving because it benefits

the author but is detrimental to the reader.

How so? Well the bigger the numbers the more awesome the

story is. Or at least that’s the idea. There are many people who think that

bigger is better, and so they go over the top. “If you think having a million

people die is sad, then just wait because I

have a trillion.” It does not, however, enhance the reader’s experience. A

trillion people is far too large a number to truly comprehend. We can’t imagine

a trillion toothpicks, let alone human beings. It doesn’t make us feel any more

than having a million die.

In this case, if the author was consider what would have the best effect on his audience rather than what made his story look “epic,” he would be better off describing the death of two than a trillion. You could have the protagonist watch as an entire planet is blown up, but if you really wanted to make your readers care, you might just have him walk through a destroyed home where the charred remains of a father and son sit posed in their chairs, the child’s fingers clutching his dad’s collar still fully defined.

It may not press the vast importance of the war, but it

inspires more feeling in the reader than a remote explosion with people we

never meet.

Writers write for themselves and that is often the

mindset which creates the best work. You can’t deny your reasons for doing

something; most times you wouldn’t want to. Readers do want to read about epic

characters, grandiose plots, and especially good turn-a-phrase. So have those

things. Just make sure that you don’t look like you’re doing what you’re doing.